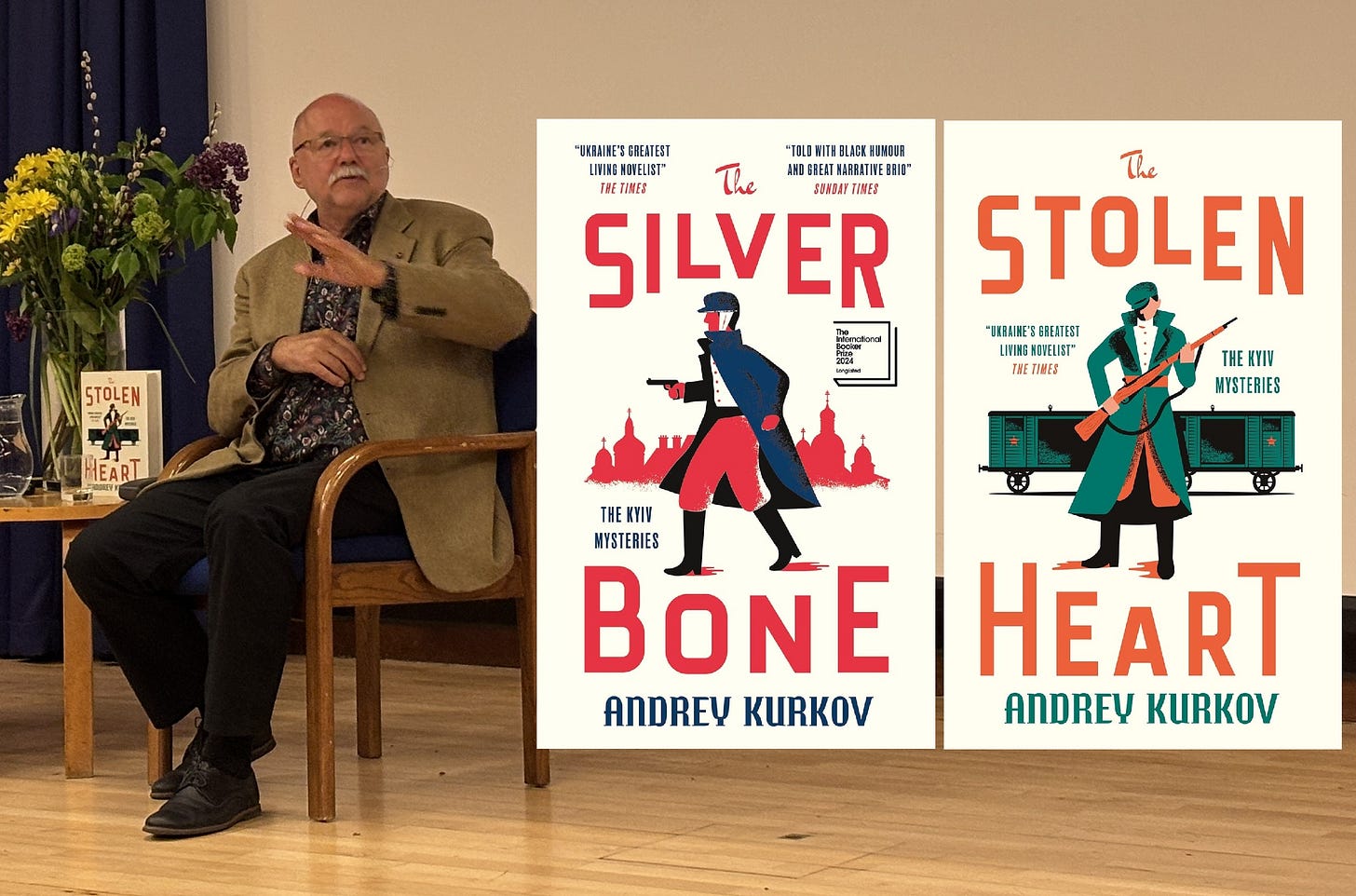

On two consecutive days I listened to Andrey Kurkov being interviewed, firstly at Daunt Books in London and then St John’s College, Cambridge. I’d already read the first of his dilogy, soon to be trilogy, of Kyiv Mysteries, The Silver Bone, a fusion of detective story and historical fiction set in Kyiv in 1919. Then I read a profile of him in The Guardian in which he confessed an admiration for my current academic obsession, Konstantin Vaginov, saying Goat Song was the book that compelled him to be a writer and traces of it could be found in The Silver Bone. I was intrigued, and quickly read the second book in the series, The Stolen Heart, just published in translation in English - the reason for his sojourn from Kyiv to promote it to his UK readership - before returning to The Silver Bone. Alas, I could find no obvious allusion or reference to either Vaginov or Goat Song and so decided to try and ask him in person.

In The Kyiv Mysteries, Kurkov brings new meaning to the sinister aphorism that walls have ears. The ear of young, recently orphaned policeman, Samson Kolechko, severed by the sabre of a Cossack horseman, lives in a sweet tin. Through a magical realist twist, and distinctive nod to Gogol, Samson can still hear through it, a signal of the absurdity of post-Revolutionary Kyiv. Between 1918 And 1921 control of the city changed thirteen, maybe fourteen times, between seven competing militias and armies, the Bolsheviks eventually establishing Soviet Power on the fourth attempt. This is a narrative, Kurkov reveals, that was never part of official Soviet history.

The Kyiv Mysteries are works of fiction informed by a cache of Cheka files given to Kurkov by a friend whose father had been a KGB general. Kurkov received the first tranche in 2017 followed by two subsequent donations: a total of fifteen kilogrammes of “human destinies”. The files contain over a thousand handwritten witness statements, accounts of interviews and confessions which, in the novels, constitute the cases Samson and his colleagues methodically work through. The laws and thus the crimes are as fluid and dynamic as the politics and administrations. The incipient violence and resistance to Ukrainian independence in various hues by the Red Army has clear parallels with present day Ukraine and the full-scale invasion of 2022.

Prior to the invasion Kurkov, author of over thirty books, resident of Kyiv and Ukraine’s foremost living writer, had written two books in the series, The Silver Bone in 2018 and The Stolen Heart in 2020, translated into English in 2024 and 2025 respectively. After the full-scale invasion Kurkov tried several times to pick up the sixty pages of the third book in the series but found he could no longer write fiction. Addressing and witnessing at firsthand what was happening became Kurkov’s immediate intellectual priority: journalism, reportage and publishing diaries. The nightly air raid sirens, drone attacks and missile bombardments presented a practical barrier to the concentration required to write fiction.

The first two novels are humorous in a wry, understated manner that highlights the absurdity of social life, something Kurkov recently divulged he now measures in Kafkas. The surrealism of political life is measured in Orwells. An Orwell is ten Kafkas. The reactions and responses of his characters to the mundane and trivial details that pepper the novels acts as a benchmark for their acceptance of the Bolsheviks and Soviet Power, marvelling when the lights burn brightly or disguising small acts of rebellion. It is echoed in the spiritual and romantic development of Samson and his girlfriend/fiancée/wife, Nadezhda. Their ‘anti-wedding’ in an ‘anti-chapel’ by an ‘anti-priest’, is facilitated by one of Samson’s colleagues, Sergius Kholodny, himself a defrocked priest who is now an atheist but still believes – although, in what, he is not certain.

The realignment of God and faith in an atheist society, in which all previous certainties have been thrown into disarray, is a fundamental theme of both books. New deities vie for ideological and spiritual supremacy. Samson’s embrace of Soviet Power is stoic, like a fellow-traveller; Nadezhda’s, who works in the Provincial Bureau of Statistics, the ProvStatBuro, is more fervent. They are both inured to the privations of war, the siege mentality of their compatriots, and the incessant transition of administrations.

Samson is an insomniac permanently on the verge of exhaustion, haunted by the slaughter of his father by the same Cossack that severed his ear. At one-point Nadezhda is kidnapped by mutinous railway workers, who object to the census she is undertaking, but is rescued by Samson in an audacious raid. Samson is happy to learn interrogation techniques; Nadezhda to be taught how to shoot a revolver. Both strive to impose a sense of normality and stability on a city that is in turmoil, the tinge of nostalgia for the old-world like the penumbra of a looming eclipse.

In The Silver Bone, Samson struggles to establish the connection between the two corrupt Red Army soldiers who take over his dead father’s study, their haul of stolen silver and expensive cloth, the pattern of a suit for a peculiarly proportioned man, a German tailor, and the elusive Jacobson. The most significant piece of evidence is a solid silver thigh bone, possibly a traditional gift from a grateful patient to a surgeon or a religious totem. Alongside his investigations and personal demons is the constant threat of thieves and bandits who operate with impunity, and the incursions of rebels and the White Army on the outskirts of Kyiv, which embroil Samson in a daily struggle for survival.

The Stolen Heart has a similar thread of connections that Samson tries to unravel, centred around the slaughter of a pig which has suddenly become illegal according to the Extraordinary Provincial Food Committee, known in contracted form as ExProFooCom. The new law sits alongside the tithe on superfluous furniture and underwear, detailed in The Silver Bone, intended to furnish the offices of the Red Army and clothe its soldiers. They exemplify the absurdity, complexity and emergent bureaucracy of Kyiv coming under the control of Soviet Power, in which Samson and Nadezhda become complicit.

Samson interviews the recipients of different cuts of meat from the carcass of the pig, helpfully annotated on a chart by the butcher, revealing further Kafkas and Orwells of life in Kyiv. He has to contend with his increasingly impatient boss, Comrade Nayden, and the ignominy of a thief operating in the police station. Again, it is Samson’s steady progress, learning procedures from old tsarist case files, combined with an understanding of human motivation, that allows him to reach a conclusion, albeit one that fails to satisfy the Cheka agent assigned to oversee the effectiveness of Nayden’s operation and of Samson’s competence.

Pork, or rather the lack of it, pork fat and cured pigs’ ears, a delicacy given to Samson by Li Yin Jun, a Chinese Red Army soldier who helped him rescue Nadezhda, all highlight the shortage of food and the possible motivations for illegal butchery. Sounds and smells powerfully evoke the Kyiv of 1919 – the cracks of gunshots, kerosene and kasha, holy candles and incense, fresh blood, the stench of urine and horses’ hooves on cobblestones. Samson, in a moment of surreal reflection, holds his severed ear next to a dried pig’s ear.

The pork had a strong smell, while his own ear gave off a barely perceptible spicy odour, like a fresh basil leaf.

The sweet tin in which he keeps his ear is effectively a reliquary. It also contains the two bullets that almost killed Samson when he was shot by Jacobson, their gunfight the denouement to The Silver Bone. The contents remind Samson of his own mortality - the ear has saved his life more than once - but also embody his faith in an alternative to Soviet Power. The final scene of The Stolen Heart is a public bathhouse, from which twenty naked Red Army men suddenly disappear. This is the next Kyiv Mystery Samson must solve, which might also reveal what further talismans he has placed in his tin to afford himself and Nadezhda protection.

Prior to entering Daunt Books in Marylebone I enjoyed a pre-event glass of wine in a nearby comptoir. It was expensive, small and extremely tasty unlike the glass handed out in the bookshop, which was notionally free (included in the price of the entry ticket), meagre and bland. The London evening was sunny but cool which explains the preponderance of gilets parading up and down the High Street, mine included, but I didn’t have an American accent and, as a recovering technologist, no longer count as a tech bro. I had mentally prepared my question about Vaginov and Goat Song but worried that it was both banal in the context of the war and esoteric in the context of literature.

Nonetheless, I grabbed a seat near the front and waited patiently whilst the audience slowly gathered behind me; their ripples of grey hair seemed to have been specially coordinated with the eponymous silver bone. Attendance was sparse, which was disappointing, because I had heard Kurkov complain that the logistics of travelling to just about anywhere from Kyiv meant that the round trip took four days. For him to leave he needed to be certain it would be worth his while.

Having navigated the fine line between talking about literature, talking about the war, and talking about literature and the war, Kurkov’s interlocutor opened up the proceedings for audience questions. I was still in two minds but when he was asked about the resonance of Tolstoy’s writing and to tell a joke - which involved Mitterrand, Reagan, Putin, the devil and a large black telephone, and typified his bleak sense of humour - I decided to thrust my hand in the air.

Kurkov explained the trace of Vaginov was that Goat Song was set at the same time as the Kyiv Mysteries and also featured Chinese Red Army soldiers. They had originally come to Russia to work on the construction of railways prior to the Revolution and were based in Saint Petersburg. After the Revolution it was more expedient to join the Red Army than return home and around 5,000 were dispatched to Kyiv. Some also joined as professional revolutionaries. Regardless of their background they were found to be more reliable and more disciplined than their Slavic counterparts, who displayed a non-Bolshevik inclination to show mercy to their compatriots.

My problem was that there were no Chinese Red Army soldiers in Goat Song. So, I purchased Kurkov’s most recent non-fiction book, his war-time diary, Our Daily War, and broke my rule about not joining the signing queue at the end of a book reading event. Having proffered Kurkov the book, I engaged him again about Vaginov. He gave a similar explanation and wondered if I enjoyed Goat Song, correctly guessing that I had not read it in Russian. I said I loved it. Kurkov elaborated that he was originally given a copy when he was a teenager by a visiting American professor and the image of the Chinese Red Army soldier has stayed with him ever since. When I suggested that, having read the book multiple times, I didn’t recall such an image he thought for a moment and then wondered if perhaps he was thinking of Mandelstam.

I subsequently found one chapter in Goat Song where a group of Chinese men, who make paper decorations, are living in a communal apartment. One has had a child with the cleaner, a tiny waif who declares to the character known as the philosopher who also lives there that she is a ‘Russkie’. Her father returns to China, her mother has an affair with another of the Chinese man but dies from an unsuccessful abortion. The professor effectively adopts the child who he thinks resembles a cat, leaving her a saucer of milk in a corner of his room and occasionally letting her run around in the courtyard. Eventually he provides her a bed and new clothes, but he is acting from logic because she had nowhere else to go rather than from kindness. I’m sure that Vaginov intended this as some kind of allegory but am not at all sure what he meant.

With my question answered and my curiosity partially sated, I approached the second event with less determination. I had been pondering the notable shifts in mood the previous evening. As Kurkov got figuratively closer to home his enthusiasm and humour inevitably dissipated. He had let out a big sigh as he began to address the war, and it immediately became obvious why writing fiction set in the present wasn’t just an impossibility from a psychological and practical perspective but also from a moral one. It was simply wrong, he had explained, to try and fictionalise events and to invent characters when reality presented a far more chilling narrative. It was a theme he returned to in Cambridge, further elaborating on the “immorality” of writing fiction; a pleasure that in war becomes a guilty one, as does reading fiction.

Kurkov eventually managed to complete the third Kyiv Mystery in November last year, has started a fourth and hinted at the plot for a fifth, but still finds it impossible to write fictional accounts of the present day. The historical setting of the mysteries affords him a necessary psychological and emotional distance. “I can hide in the past” he explained in a recent interview. His Kyiv novels have become a fictional reality that allow him to detach from the present, the wars Kyiv faced after the Revolution are his hiding place from the current war.

It is the moments of absurdity that are the novels’ most realistic and the ones that feed their humour. What fascinated him about the Cheka files was how they revealed “the stupidity of the local Bolshevik functionaries”. In his youth humour was the preferred genre of intellectuals and dissidents. It was and is a form of “psychological protection”, and why it is so fundamental to his novels. However, his fiction is more violent now – not something he likes, reluctantly admitting what he thought was a thing of the past is endemic in the present – and, having regained his sense of humour, finds it is darker than before.

The first three books are set in consecutive months, March, April and May 1919 and the third, apparently, sees the White Army temporarily recapture Kyiv. But the mysteries were not the first books he set in post-Revolutionary Kyiv. The city is the backdrop for part of The Geography of a Single Gunshot, a trilogy written over seven years and published in 2003 in which he tried to comprehend the development of the Soviet mentality. It has never been translated into English, and he thought it might now be of limited interest to an English-speaking readership. Although Kyiv is the geographic locus of both trilogies, it could be argued that his intellectual focus has fundamentally shifted from the Soviet psyche to the Ukrainian one.

The Cambridge event, part of a literary festival, was in a modern lecture theatre, not the promised beautiful and historic venue I had been expecting, but once inside St John’s I took the opportunity to skulk around the cloisters and found myself ambling over the covered Bridge Of Sighs from one quadrangle to another. The Google Maps route from the station had taken me the long way round and through the unprepossessing back entrance to the college. I left through the front door although that phrase doesn’t do justice to the grandiose entrance or the envious tourists craning their necks for a better view. The students meanwhile were impervious to tourists and festival goers alike, playing games on the immaculate lawns and swigging champagne. Earlier, I’d enjoyed a glass of chardonnay in a pub that claimed C. S. Lewis and Tolkien as prior literary patrons but knew my foray into the academic bastion would be short lived.

Kurkov must have been delighted when he walked onto the stage and saw a packed audience, far larger than the previous night, and seemed genuinely touched by the extended applause at the end. He appeared to be more positive about the outcome of the war and talked about the new generation of poets, writers and artists at the forefront of a Ukrainian culture offensive that eschews anything tinged with Russia. A recurring theme in all of Kurkov’s ongoing commentary is that, on one level, the war is an assault on Ukrainian identity. Inevitably, language is a battlefield.

In the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas the Ukrainian language is once again banned and the libraries that remain undamaged are now being emptied of Ukrainian books and filled with classic Russian novels. In Ukraine, language is a marker of patriotism. Shops no longer stock Russian-language books and there is no interest in reading classic or contemporary Russian literature, which has been weaponised by Putin’s imperialism. Kurkov, whose mother-tongue is Russian, writes journalism and books for children in Ukrainian but fiction in Russian which is then translated. He has no idea how his recent novels have been received in Ukraine as they are not reviewed and his voice has effectively been cancelled by some Ukrainian intellectuals who objected to his appearance alongside Masha Gessen, a prominent Russian opponent of the war.

Kurkov explained that the heroes of the Kyiv Mysteries are professionals who, under the most extreme of circumstances, want to preserve their morality. This is a characterisation that surely applies to Kurkov himself. The fictional Kafkas and Orwells of Kyiv in 1919 have their corollaries in the present day, poignantly documented in Kurkov’s diary entries. Our Daily Way, spanning August 2022 to April 2024, an essential companion to the Kyiv Mysteries, is a commentary that doesn’t have the psychological, emotional or historic distance to avoid it being tragic rather than comic.